This material (including images) is copyrighted!. See my copyright notice for fair use practices. Select the photographs to display the original source in another window. Most of the ground-based telescope pictures here are from the Anglo-Australian Observatory (AAO---used by permission). Links to external sites will be displayed in another window.

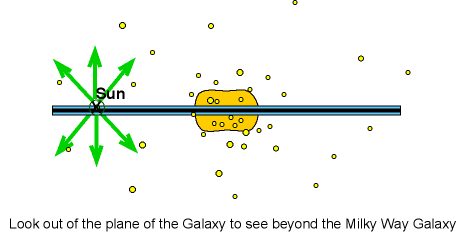

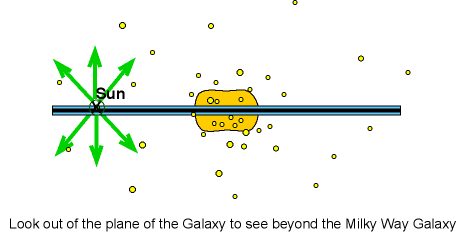

If you are sitting in an ordinary chair, lean over and look at the ground directly below your head. A cylinder the diameter of your eye drawn from your eye to the ground would enclose about as many particles of air as there are interstellar particles in a cylinder of the same diameter but extending between our solar system and the center of our galaxy 27,000 light years away. Though the space between the stars is emptier than the best vacuums created on the Earth (those are enclosed spaces devoid of matter, not the household cleaning appliances), there is some material between the stars composed of gas and dust. This material is called the interstellar medium. The interstellar medium makes up between 10 to 15% of the visible mass of the Milky Way. About 99% of the material is gas and the rest is "dust". Although the dust makes up only about 1% of the interstellar medium, it has a much greater effect on the starlight in the visible band---we can see out only roughly 6000 light years in the plane of the Galaxy because of the dust. Without the dust, we would be able to see through the entire 100,000 light year disk of the Galaxy. Observations of other galaxies are done by looking up or down out of the plane of the Galaxy. Dust provides a place for molecules to form. Finally, probably the most of important of all is that stars and planets form from dust-filled clouds. Therefore, let us look at the dust first and then go on to the gas. The structure of the Galaxy is mapped from measurements of the gas.

The discovery of the dust is relatively recent. In 1930 R.J.

Trumpler (lived 1886--1956) plotted the angular diameter of star

clusters

vs. the distance to the clusters. He

derived the distances from the inverse square law of brightness:

clusters farther away should appear dimmer.

IF clusters all have roughly the same

linear diameter L, then the angular diameter

![]() should

equal a (constant L) / distance. But he found a

systematic increase of the linear size of the clusters with

distance.

should

equal a (constant L) / distance. But he found a

systematic increase of the linear size of the clusters with

distance.

This seemed unreasonable! It would mean that nature had put the Sun at a special place where the size of the clusters was the smallest. A more reasonable explanation uses the Copernican principle: the Sun is in a typical spot in the Galaxy. It is simply that more distant clusters have more stuff between us and cluster so that they appear fainter (farther away) than they really are. Trumpler had shown that there is dust material between the stars! The extinction of starlight is caused by the scattering of the light out of the line of sight, so less light reaches us. Now, of course, it is much easier to detect the dust once you know it is there and we can directly image it with infrared telescopes and millimeter-wavelength telescopes such as the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile.

Not all wavelengths are

scattered equally. Just as our air scatters the

bluer colors in sunlight more efficiently than the redder colors, the

amount of

extinction by the interstellar dust depends on the wavelength. The amount

of

extinction is proportional to 1/(wavelength of the light). Bluer

wavelengths

are scattered more than redder wavelengths.

Not all wavelengths are

scattered equally. Just as our air scatters the

bluer colors in sunlight more efficiently than the redder colors, the

amount of

extinction by the interstellar dust depends on the wavelength. The amount

of

extinction is proportional to 1/(wavelength of the light). Bluer

wavelengths

are scattered more than redder wavelengths.

The 1/![]() behavior of the scattering indicates

that the

dust size must

be about the wavelength of light (on the order of 10-5

centimeters). Less blue

light reaches us, so the object appears redder than it should. This effect

is

called reddening, though perhaps it should be called

"de-blueing".

If the dust particles were much larger (say, the size of

grains of sand), reddening would not be observed. If the dust particles

were much smaller (say, the size of molecules), the scattering would

behave

as 1/

behavior of the scattering indicates

that the

dust size must

be about the wavelength of light (on the order of 10-5

centimeters). Less blue

light reaches us, so the object appears redder than it should. This effect

is

called reddening, though perhaps it should be called

"de-blueing".

If the dust particles were much larger (say, the size of

grains of sand), reddening would not be observed. If the dust particles

were much smaller (say, the size of molecules), the scattering would

behave

as 1/![]() 4.

Trumpler showed that a given spectral type of star

becomes increasingly redder with distance. This discovery was

further

evidence for dust material between the stars.

If the Sun is in a typical

spot in the Galaxy, then Trumpler's observation means that more distant

stars have more dust between us and them.

4.

Trumpler showed that a given spectral type of star

becomes increasingly redder with distance. This discovery was

further

evidence for dust material between the stars.

If the Sun is in a typical

spot in the Galaxy, then Trumpler's observation means that more distant

stars have more dust between us and them.

You see the same effect when you observe the orange-red Sun close to the horizon. Objects close to the horizon are seen through more atmosphere than when they are close to zenith. At sunset the blues, greens, and some yellow are scattered out of your line of sight to the Sun and only the long waves of the orange and red light are able to move around the air and dust particles to reach your eyes.

At near-infrared (slightly longer than visible light) the dust is transparent. At longer wavelengths you can see the dust itself glowing and you can probe the structure of the dust clouds themselves as well as the stars forming in them (young stars that are hidden from us in the visible band). The Spitzer Space Telescope observes in the infrared and has opened up a new universe to us. Although it is not the first infrared space telescope, it is the largest infrared space telescope still in operation, so it has the greatest light-gathering power and resolution of any infrared telescope. The Herschel Space Observatory (see also NASA site) had an even larger mirror than Spitzer but observed in longer infrared wavelengths. Herschel was active from 2009 to 2013. Spitzer, launched in 2003, remains active today. A couple of examples of the power of infrared I use in my class are the movie of the dark globulae IC 1396 and the movie of Herbig-Haro 46/47 on the Spitzer images site that transitions from the visible light image to the near infrared to the mid-infrared. Other movies contrasting the views at visible with infrared of other places in the galaxy as well as other galaxies are available there too. The superior resolution at millimeter wavelengths of ALMA has enabled us to see planets forming in the dust-filled protoplanetary disks around young stars.

| dust | extinction | interstellar medium |

|---|---|---|

| reddening |

![]() Go back to previous section --

Go back to previous section --

![]() Go to next section

Go to next section

last updated: June 27, 2022